by Gregor Tarjan, Aeroyacht Ltd.

Catamaran Advantages vs. Monohulls: Zero Heel and Flat Sailing

Zero angle of heels makes catamarans the ultimate safety platforms to sail the seas. Cruising catamarans are safer than monohulls because they provide a better shelter and a no-heel environment for their crew. This will result in less exposure, fewer seamanship errors caused by fatigue and a more refreshed crew at the end of a long trip.

I remember sailing into the middle of the Miami Boat Show with “Alize”, a magnificent 64’ catamaran after crossing the North Atlantic. The boat show with 1000’s of visitors was our first landfall after 6,000 miles of non-stop sailing. Although the vessel was big and comfortable, the crossing was challenging as we experienced very rough weather after leaving the Canary Islands. Trying to sneak out of the Mediterranean Sea in the middle of winter with inches of snow on deck and fierce headwinds was not easy either. Yet at the end of the voyage my three crewmembers were in top form and the boat looked as if she just came out of the factory. The most amazing fact is that nothing major failed on this maiden voyage. She barely had 100 miles on her log before leaving the South of France. Maybe things would have been different on a monohull, which could not protect her crew from the elements as well. During the three days of the Canary storm the boat was sailing under autopilot at speeds of 20 knots and we once even hit 28 knots without touching the helm. Even in these rough conditions we found ourselves sitting around the stable saloon table eating three course meals and enjoying fine French wine. (The bilges of the boat contained 100’s of bottles). Sitting at dinner, riding down huge waves, the feeling and atmosphere on the bridge deck was alert but definitely less stressed than it would have been on a monohull. I have been on 65’ monohulls in less severe conditions and it certainly felt worse. Imagine sailing on a heeling boat in a storm and having to hand steer, unprotected at the outside helm. Chances are high that in those conditions and speeds the autopilot of a monohull could not hold the boat as easily, since the single rudder and keel would constantly yaw and change the angle of attack. The resulting cavitations and pressure could disengage the pilot at the most inopportune moment and result in a broach or even worse. Exposure to the helmsman who would be forced to hand steer for hours would be unbearable and rotation of crew would be necessary. Fatigue would take its toll and making tactical decisions when one is tired is the number one cause of seamanship errors. We were mostly in the cockpit behind the protection of the coach roof, letting the autopilot do its work. We only took one single breaker into the cockpit when the boat accelerated overtaking seas. She buried a good part of her twin bows into the next wave face and the resulting impact created a deluge that drenched us 50’ back in the cockpit, but that was it. The twin rudders, usually protected either by skegs or mini keels, always remained vertical, greatly assisting the function of the autopilot. The long slender hulls also contributed to directional stability of our catamaran, which would have been in total contrast to the constant change of attitude of a monohull.

While at the subject of underwater appendages; on the transatlantic passage with “Alize” we collided with a whale in the storm and did not even notice it because of the tumultuous circumstances. It was quite apparent when I stood at the dock in Miami admiring the boat with her owner when we realized that one of the 4’ deep hull skegs was completely sheared off. It did what it was intended to do and sacrificed itself to save the spade rudder located just aft of it. Imagine a missing single rudder on a monohull in the middle of a storm. It would be a major incident, thus substantiating the safety feature represented by the twin engines of a multihull. If one fails, you still have another to get you home. I think it is quite apparent that a well designed, unsinkable, fast multihull with duplicate systems, providing better shelter and a non heeling environment will simply be a safer boat than a monohull.

A catamarans absence of heeling becomes a fact of life on a multihull. Zero angle of heel on a multihull goes beyond the discussion of safety as it is easy to understand that performing every-day tasks on the level become increasingly difficult when heeling. Most importantly, falling overboard and perishing at sea is the single most cause for fatalities at sea and has happened even to the most experienced sailors. (eg. the tragic disappearance of the famous sailor Eric Tabarly off his own monohull). Slipping off the stable deck of a wide catamaran is less likely. Even retrieving a man overboard victim is difficult on a monohull and famous ocean racer, Rob James, who slipped off his trimaran “Colt Cars”, died of exposure before he could be retrieved. Interestingly, most drowned sailors are found with the fly of their trousers open, which says it all. The fact is apparent that it is much less likely for a sailor to fall overboard from a stable catamaran than a heeling monohull.

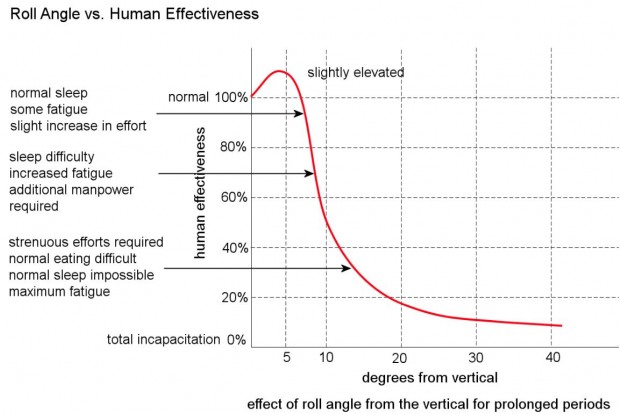

The Navy published an interesting study years ago, in which test subjects were exposed to different responsibilities at varying angles of roll and heel. Interestingly, the effectiveness and degree of alertness of sailors increased up to 3 degrees of heel but radically diminished as time, roll angle and heel angle increased.

A stable catamaran’s advantages become quite clear when performing the most mundane maneuvers. Did you ever try going to the toilet, even in moderate conditions, on a monohull? It is often an act of great contortions and almost comical in nature. One is balancing, trying to anticipate the ship’s motion and looks not to mess up body and environment. In storm conditions visiting the head on a monohull becomes dangerous. The confined space brings one’s head in close proximity to the handles and edges and I have often been thinking of investing into a crash helmet before going to the toilet. It is not to say that the experience on a catamaran it is less violent, but at least one does not have to deal with the additional gymnastics needed to compensate for the heel factor. I have seen many burns on chest and under-arms and heard countless horror stories of pots of boiling water flying through monohull cabins. On a single hulled vessel there are even sadistic straps for the cook to tie him to the stove, leaving little movement to escape from danger. It is very rare that cooking gear needs to be clamped to a stove on a catamaran. Catamaran galleys are definitely safer places to handle scalding dishes and in the worst conditions bottles remain upright if placed into the sink. There is a reason I have never seen a gimbaled stove or a cantilevered saloon table on a catamaran. Fiddles and door locking mechanisms are often necessary on monohulls to prevent items becoming airborne. On a stable catamaran, wine glasses will remain on tables up to Force 8 conditions!